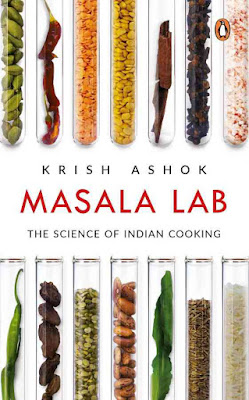

An excerpt from Krish Ashok’s ‘Masala Lab’, an exploration of the science of Indian cooking.

Armchair-uncleji theories about how tropical parts of the world do not have brewing traditions because of their climate are patently silly. When you put human beings, carbohydrates and some microbes together, alcoholic drinks will emerge. [...] When you ferment things, ethanol is almost always produced. There is no escaping it.

If you make yoghurt at home, it will have a tiny amount of ethanol that is produced by wild yeast in the environment. Industrially produced yoghurt is fermented in sterile conditions to ensure that only specific strains of bacteria, such as streptococcus thermophilus and lactobacillus lactis, feast on the milk sugars and do not produce alcohol. This is also why homemade yoghurt is almost always richer in flavour, because a diversity of microbes results in more complex flavours. And some alcohol.

|

Representational image. | The Bombay Canteen/Facebook |

If you bake bread, there is literally no escaping alcohol production. Yeast produces alcohol when it eats up sugars. In fact, one element of the sweet smell of baking bread is the ethanol evaporating. The alcohol molecule has a slight resemblance to the sugar molecule, which is why, in low concentrations, it tastes sweet. Breads, such as naan, made after a long fermentation process with yeast can sometimes contain about 2 per cent residual alcohol even after baking. Leave aside bread-bakers and naan-makers, the long-standing tradition of eating rice fermented overnight involves consuming a finished product that can be pretty alcoholic. Now you know why people eat fermented rice with raw onions soaked in yoghurt in south India. The onions overpower the smell of alcohol.

I want you to consider using alcohol in moderate amounts while cooking process. You don’t have to drink it, and rest assured, your finished product will not be any more alcoholic than the bread you bake or the yoghurt you ferment.

[...] If you remember, flavour is a multisensory experience that involves the taste buds, nose, ears, eyes and mouthfeel. Among these, aroma contributes to about 80 per cent of how we perceive flavour. While our tongues can detect five kinds of tastes, our noses can detect thousands of aromas. In fact, we can detect some aromas even if the concentration is of a few molecules in a trillion! Sulphur-based aroma molecules, like the smell of cooked fish, tend to be detectable at concentration levels approaching one molecule in a quadrillion!

This is a crucial thing to remember when making good food – we can only taste things that are water-soluble, but we can smell way more volatile aroma molecules thanks to the olfactory receptors in our noses. Most spices and strongly aromatic ingredients have volatile flavour molecules that are not water-soluble, so we can’t actually taste them.

Remember, you smell cardamom, you don’t taste it. What you taste when you bite into cardamom is its woody mouthfeel and bitter taste. This is why fats are absolutely crucial to cooking, because most flavour molecules are fat-soluble, not water-soluble.

This means that when you cook spices in hot oil, it extracts all of these flavour molecules and dissolves them into the oil, thus preventing them from being lost to the air. When you eat this food, the enzymes in your saliva start breaking down the fats, which results in those dissolved aroma molecules escaping into your mouth. As they enter the short, shared highway that transports both food and air, the act of breathing out elevates the aroma molecules, which are basically gases, and makes them hit the olfactory receptors. That is when you truly experience the complex taste of the thousands of aroma molecules from the saffron in your biryani.

Now that I have your attention with the words ‘saffron’ and ‘biryani’ (no political angle here, I assure you), let me tell you that after fats, the silver medal winner in the 100 m flavour extraction race is alcohol. A tiny amount of alcohol used while cooking will almost always result in a stronger flavour. The alcohol will help transport more aroma molecules to your nose and make your dish pop.

Here is how I use alcohol when making Indian dishes:

- A splash of vodka, brandy or rum when cooking onions, ginger, garlic, tomatoes and spice powders has two benefits: extraction of more flavour from the spices and the alcohol’s ability to release all those sticky bits from the bottom of the pan, which have a ton of flavour thanks to the Maillard reaction.

- A splash of wine added at the end of a dish, along with finishing spices, will amplify the effect of those spices when you eat.

- Keep in mind that while a small amount of alcohol can amplify flavour, a large amount will actually prevent the release of flavour molecules by holding on to them like family heirlooms. This is incidentally one of the reasons why bar snacks tend to be overpoweringly spicy in India. When had with a large whisky, that mirchi bajji could well be made using bhut jolokia chillies and you won’t notice.

- The amount of alcohol in beer is not strong enough to make a difference, so at the very least, use wine. The cheapest one will do because once heated, all the evocative notes of strawberries and smoked salmon in your fine Chardonnay will largely be destroyed. You can, however, use beer as an acid.

- If you are frying fish (or vegetables) using a batter, try a batter made of maida, salt and vodka (which is just plain ethanol diluted in water). What the alcohol does is reduce gluten development, which we do not want in a fried product, as it will cause chewiness. It also prevents surface starches from absorbing too much water to gelatinize, which will result in a drier and crispier crust. This technique was pioneered by Heston Blumenthal, who went one step further and carbonated his batter before use. The aerated batter makes the crust airy, in addition to being crisp. Trust me, use this technique and you will have some game-changing pakoras to enjoy.

Excerpted with permission from Masala Lab: The Science of Indian Cooking, Krish Ashok, Penguin Books.

(Source: Scroll)

No comments:

Post a Comment