In 1968 Ida Lupino was the sole female director to merit an entry in Andrew Sarris’s auteur bible The American Cinema: Directors and Directions 1929-1968. Lupino’s films were dismissed in a sentence; the rest of Sarris’s pithy capsule drew attention to a “ladies’ auxiliary” in cinema, listing notable female directors of the silent era and later, as well as those “the jury is still out on” (Shirley Clarke, Vera Chytilová and Agnès Varda among them). Dorothy Arzner, who directed 13 films after 1929 (plus two she was not credited for), only gets mentioned as an auxiliary.

Although he didn’t question why there was such a paucity of female directors, Sarris at least highlighted the fact at a time when few others did, and extended his search for them beyond the US. However he needlessly resurrects Lillian Gish’s statement about directing being no job for a lady, and hardly skewers it (“Simone de Beauvoir would undoubtedly argue the contrary”).

Female directors didn’t fare much better in the pages of Sight & Sound in those years (despite a female editor, Penelope Houston), although when their films were released in the UK they received their due reviews in the then quarterly’s sister publication, Monthly Film Bulletin.

|

Illustration by Lorenzo Patrantoni for Sight & Sound © lorenzopetrantoni.com |

Before the 1980s, of those filmmakers Sarris notes, only Chytilová, Varda and Leni Riefenstahl had features written about them in S&S, in addition to animator Lotte Reiniger, the Russian auteur Larisa Shepitko and avant-gardiste Maya Deren, who he didn’t. The first time Shirley Clarke’s career was appraised in these pages was in 1998, in her obituary.

Much vital work has been done since by critics, film historians, academics and programmers to write female filmmakers back into history. The damage, though, is deep-rooted. In April this year Vanity Fair credited Lupino as “one of the first” female directors “to crack the whip”, ignoring predecessors such as Alice Guy-Blaché and Lois Weber, who were working up to 50 years before her.

As Mark Cousins points out in his Dispatches column this month (see page 11), depressing female filmmakers working today, and the (justified) internet outrage they provoke, tend to obscure those filmmakers who have gone before. Other than decrying the status quo and highlighting and critiquing new films by female directors, what can a film magazine do? Well, one option is to cast light on great female-directed films that have slipped through the net of male-auteur-centred criticism and such canon-forming exercises as Sight & Sound’s Greatest Films poll.

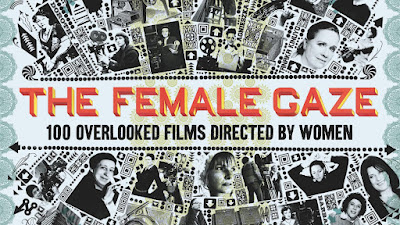

With that in mind, contributors to this feature – who range from filmmakers to critics, academics to programmers – were asked to nominate a film by a female director they believe has been forgotten or unfairly overlooked.

In August 2007, S&S produced a similar ‘Hidden Gems’ issue, unearthing 75 lost and forgotten films by men and women, which shone a light on, among others, Nicole Védrès’s Paris 1900, Sally Potter’s The Gold Diggers and Barbara Loden’s Wanda (discussed below by Isabelle Huppert).

In recent years more under-appreciated films by women have resurfaced, such as Claudia Weill’s Girlfriends (explored by both Greta Gerwig and Allison Anders). We were never in any doubt that there were more out there.

This list’s focus is primarily the 20th century – before the democratising advance of digital technology made it easier for women to make films, and the galvanising force of the internet enabled a wider critical advocacy; but also to ameliorate short-term memory syndromes.

The list is dominated by features, since these need more money and support of the kind that’s been in short supply for female directors since the silent era – in the world of avant-garde short films, by contrast, women have faced men on more equal terms, and have enjoyed more success and critical esteem.

‘Forgotten’ and ‘overlooked’ are nebulous terms, particularly in the internet age, when everything is supposedly rediscovered, and our list of 100 films reflects that – including both undeniable obscurities (The Enchanted Desna by Yuliya Solntseva, who was name-checked by Sarris merely as “Dovzhenko’s widow”), as well as films by relatively lauded directors (such as Elaine May and Kira Muratova) that are either hard to find or not regarded nearly as highly as we feel they should be.

Sadly, a far simpler proposition would be to note those female filmmakers who are appreciated, and whose work is regularly seen in cinemas – though such a shortlist might reveal still deeper problems, dominated as it would be by white Europeans and Americans.

Few female filmmakers have had the luxury of making more than a couple of features. So how do you achieve auteur status with so few films to your name? And how much more quickly do your films fade from history as a result? As the number of films listed here by actresses turned directors shows, women have often had to acquire power in front of the camera before being allowed behind it.

Also included are films that stood at the edges of famous movements in cinema (Jacqueline Audry’s Les Petits Matins and the French New Wave, Lorenza Mazzetti’s Together and Free Cinema, Li Hong’s Out of Phoenix Bridge and China’s New Documentary Movement), which were obscured by the work of more renowned and prolific male directors.

Revealing, too, is the surprising number of female filmmakers who died tragically young: Barbara Loden, Sara Gómez, Kathleen Collins, Larisa Shepitko, whose films are highlighted here, but also Nicole Védrès and Forough Farrokhzad.

Of course, looking only at directors masks those women who work in other film industry roles – particularly those in the silent era, when women played a major part in all facets of filmmaking. As the only two female directors working in the Hollywood studios from the 1930s to the 60s, Ida Lupino and Dorothy Arzner were obviously important, but their careers don’t tell the whole story of women’s work and influence in the dream factory (see Mark Cousins’s previous S&S Dispatches columns on female editors or Lizzie Francke’s excellent book Script Girls). Nor should it obscure the fact that women were making great films outside Hollywood at that time – in the UK, Norway, Mexico, China and beyond.

Time for a disclaimer: this list is far from definitive, but we hope it gives a sense of some of the great, unduly neglected films made by women throughout film history from all over the world – and of the many others.

— Isabel Stevens

For further reading and the list of 100 movies head to BFI.

No comments:

Post a Comment