Only 2500 people in Jalgaon, Jahod speak Nihali. Can the answers to this language be found, before it’s completely forgotten?

The data from People’s Linguistic Survey Of India showed that India had 780 of the world’s living languages, more than 10% of the total number of languages in the world. While the survey has been widely criticised by academics, it states that India has ‘lost’ 250 languages in the past 50 years with another 150 languages which have been predicted to disappear in the next 50 years. The death of current speakers and the inability of the future generations to learn or speak the language may spell doom for such regional and tribal languages in a country where the government seems more inclined to push for greater adoption of Hindi. It’s in such a climate that the story of one of India’s oldest and perhaps her most unique language becomes even more critical.

Nihali is a language spoken in Jalgaon Jahod in Maharashtra by close to 2,500 people of the region. “There are five language families in India. Nihali, the language which is spoken there, cannot be considered belonging to any of these five langauges?” says Dr Shailendra Mohan, associate professor in Austro-Asiatic linguistics at Deccan College Postgraduate and Research Institute in Pune. Dr Mohan had taken up the studying of lesser known languages as a part of his research while studying at Jawaharlal Nehru University in Delhi and received a grant to begin the first documentation of Nihali ,from the Endangered Languages Project by the school of Oriental and African studies in London in 2012.

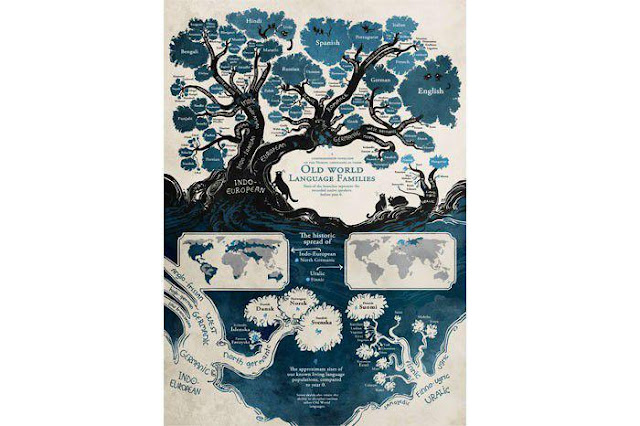

The languages in India can be grouped into Indo-Aryan, Dravidian, Tibeto-Burman, Austro-Asiatic or Andaman language families but Nihali is said to be a ‘language isolate’. Mohan told the Indian Express in 2014 explaining how hand is referred to as ‘haath’ in Marathi and ‘hatha’ in Punjabi, adding,’ These regions are miles away from each other, yet their lexicon is derived from one family of language: Indo Aryan. But Nihali does not belong to any of the four Indian language families.’ “I have submitted the reports, which I was required to but I will be continuing with the research because there are many hypotheses which can be applied to that language,” Dr Mohan told Homegrown.

Shailendra describes the process of unravelling the language and the history of the people who speak it as a ‘lifetime puzzle’ as he formulates multiple hypotheses—are the inhabitants of the region who speak the language one of the oldest in the country? Did they migrate to India? The status of Nihali has been a matter of debate for some who questioned whether Nihali could even be called a language though Dr Mohan states that Nihali is certainly a language, which will be justified with the publications on Nihali that he may soon put out in public. He is also trying to understand the reasons for Nihali’s near extinction. He seeks to not just document the language but even understand the reasons for Nihali’s near extinction.

“As you know, there is a three language formula. The local languages are never taught as you are either taught English, Hindi or Marathi,” says Dr Mohan as he tells us that no tribal language is taught in the schools of Maharashtra though some in regions like Yeotmal , where communities have made some efforts to bolster tribal and local languages. “The locals who speak Nihali, have inter-married with speakers of other languages like Marathi, Korku and Hindi. Even if a child speaks Nihali at home, once he enters a classroom, he instantly switches to Marathi. A language stays alive only when parents speak the mother tongue with their children. I don’t see that happening with Nihali. When the next two generations pass by, there is a possibility that the language might vanish with them,” said Dr Mohan after having observed the ground situation at Jalgaon Jamod closely.

There was no government support in the region or an academic body, which would support this kind of research which meant that Shailendra had to go and establish trust and contact with the locals. He would make repeated trips to the schools and town offices, attending panchayat meetings and even asked for the Sarpanch’s help. He would listen to village elders tell folk stories and songs in broken Nihali, which revealed how rich their history and mythology really was, with the locals having their own version of the Panchatantra or fables with animals at their centre, and while they sang songs from the Ramayana, they would worship Ravana as their hero. Nihali is said to have a unique sound pattern where water is ‘joppo’, to eat is ‘ti’ and drink is ‘delen.’ Dr Mohan also aims to release the first tri-lingual dictionary with Nihali-English-Hindi translations with up to 2,000 words. Dr Mohan’s efforts have met with approval from the locals who appreciate someone recording their songs, stories and lifestyle.

“Language changes unconsciously, we do not realise it during every day use. But the documentation programme has inculcated a sensitivity towards their language. They are now aware that their language is different from other communities and that there are less number of speakers,” he said in 2014. When we questioned him on the means by which Nihali could be preserved, he suggested preparing Nihali based teaching materials and teaching Nihali in schools as a medium of instruction whereby one increases the vitality of the language, while one documents the lifestyle, grammar and words of the language through dictionaries and awareness of its extinction among the speakers of the language, efforts which he has already undertaken.

While the task of unraveling undocumented history through language is ardous, Dr Mohan certainly seems to be committed to the cause. The questions of the language’s orgins, the history of the people and its impact on Indian history are profound but none are as pertinent whether the answers can be found before the language is forgotten.

(source: Home Grown)

The data from People’s Linguistic Survey Of India showed that India had 780 of the world’s living languages, more than 10% of the total number of languages in the world. While the survey has been widely criticised by academics, it states that India has ‘lost’ 250 languages in the past 50 years with another 150 languages which have been predicted to disappear in the next 50 years. The death of current speakers and the inability of the future generations to learn or speak the language may spell doom for such regional and tribal languages in a country where the government seems more inclined to push for greater adoption of Hindi. It’s in such a climate that the story of one of India’s oldest and perhaps her most unique language becomes even more critical.

Nihali is a language spoken in Jalgaon Jahod in Maharashtra by close to 2,500 people of the region. “There are five language families in India. Nihali, the language which is spoken there, cannot be considered belonging to any of these five langauges?” says Dr Shailendra Mohan, associate professor in Austro-Asiatic linguistics at Deccan College Postgraduate and Research Institute in Pune. Dr Mohan had taken up the studying of lesser known languages as a part of his research while studying at Jawaharlal Nehru University in Delhi and received a grant to begin the first documentation of Nihali ,from the Endangered Languages Project by the school of Oriental and African studies in London in 2012.

The languages in India can be grouped into Indo-Aryan, Dravidian, Tibeto-Burman, Austro-Asiatic or Andaman language families but Nihali is said to be a ‘language isolate’. Mohan told the Indian Express in 2014 explaining how hand is referred to as ‘haath’ in Marathi and ‘hatha’ in Punjabi, adding,’ These regions are miles away from each other, yet their lexicon is derived from one family of language: Indo Aryan. But Nihali does not belong to any of the four Indian language families.’ “I have submitted the reports, which I was required to but I will be continuing with the research because there are many hypotheses which can be applied to that language,” Dr Mohan told Homegrown.

Shailendra describes the process of unravelling the language and the history of the people who speak it as a ‘lifetime puzzle’ as he formulates multiple hypotheses—are the inhabitants of the region who speak the language one of the oldest in the country? Did they migrate to India? The status of Nihali has been a matter of debate for some who questioned whether Nihali could even be called a language though Dr Mohan states that Nihali is certainly a language, which will be justified with the publications on Nihali that he may soon put out in public. He is also trying to understand the reasons for Nihali’s near extinction. He seeks to not just document the language but even understand the reasons for Nihali’s near extinction.

“As you know, there is a three language formula. The local languages are never taught as you are either taught English, Hindi or Marathi,” says Dr Mohan as he tells us that no tribal language is taught in the schools of Maharashtra though some in regions like Yeotmal , where communities have made some efforts to bolster tribal and local languages. “The locals who speak Nihali, have inter-married with speakers of other languages like Marathi, Korku and Hindi. Even if a child speaks Nihali at home, once he enters a classroom, he instantly switches to Marathi. A language stays alive only when parents speak the mother tongue with their children. I don’t see that happening with Nihali. When the next two generations pass by, there is a possibility that the language might vanish with them,” said Dr Mohan after having observed the ground situation at Jalgaon Jamod closely.

There was no government support in the region or an academic body, which would support this kind of research which meant that Shailendra had to go and establish trust and contact with the locals. He would make repeated trips to the schools and town offices, attending panchayat meetings and even asked for the Sarpanch’s help. He would listen to village elders tell folk stories and songs in broken Nihali, which revealed how rich their history and mythology really was, with the locals having their own version of the Panchatantra or fables with animals at their centre, and while they sang songs from the Ramayana, they would worship Ravana as their hero. Nihali is said to have a unique sound pattern where water is ‘joppo’, to eat is ‘ti’ and drink is ‘delen.’ Dr Mohan also aims to release the first tri-lingual dictionary with Nihali-English-Hindi translations with up to 2,000 words. Dr Mohan’s efforts have met with approval from the locals who appreciate someone recording their songs, stories and lifestyle.

“Language changes unconsciously, we do not realise it during every day use. But the documentation programme has inculcated a sensitivity towards their language. They are now aware that their language is different from other communities and that there are less number of speakers,” he said in 2014. When we questioned him on the means by which Nihali could be preserved, he suggested preparing Nihali based teaching materials and teaching Nihali in schools as a medium of instruction whereby one increases the vitality of the language, while one documents the lifestyle, grammar and words of the language through dictionaries and awareness of its extinction among the speakers of the language, efforts which he has already undertaken.

While the task of unraveling undocumented history through language is ardous, Dr Mohan certainly seems to be committed to the cause. The questions of the language’s orgins, the history of the people and its impact on Indian history are profound but none are as pertinent whether the answers can be found before the language is forgotten.

(source: Home Grown)

No comments:

Post a Comment