The US news media devotes startlingly little time to climate change – how can newsrooms cover it in ways that will finally resonate with their audiences?

Last summer, during the deadliest wildfire season in California’s history, MSNBC’s Chris Hayes got into a revealing Twitter discussion about why US television doesn’t much cover climate change. Elon Green, an editor at Longform, had tweeted, “Sure would be nice if our news networks – the only outlets that can force change in this country – would cover it with commensurate urgency.” Hayes (who is an editor at large for the Nation) replied that his program had tried. Which was true: in 2016, All In With Chris Hayes spent an entire week highlighting the impact of climate change in the US as part of a look at the issues that Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump were ignoring. The problem, Hayes tweeted, was that “every single time we’ve covered [climate change] it’s been a palpable ratings killer. So the incentives are not great.”

The Twittersphere pounced. “TV used to be obligated to put on programming for the public good even if it didn’t get good ratings. What happened to that?” asked @JThomasAlbert. @GalJaya said, “Your ‘ratings killer’ argument against covering #climatechange is the reverse of that used during the 2016 primary when corporate media justified gifting Trump $5 billion in free air time because ‘it was good for ratings,’ with disastrous results for the nation.”

When @mikebaird17 urged Hayes to invite Katharine Hayhoe of Texas Tech University, one of the best climate science communicators around, on to his show, she tweeted that All In had canceled on her twice – once when “I was literally in the studio w[ith] the earpiece in my ear” – and so she wouldn’t waste any more time on it.

“Wait, we did that?” Hayes tweeted back. “I’m very very sorry that happened.”

This spring Hayes redeemed himself, airing perhaps the best coverage on American television yet of the Green New Deal. All In devoted its entire 29 March broadcast to analyzing the congressional resolution, co-sponsored by Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Senator Ed Markey, which outlines a plan to mobilize the United States to stave off climate disaster and, in the process, create millions of green jobs. In a shrewd answer to the ratings challenge, Hayes booked Ocasio-Cortez, the most charismatic US politician of the moment, for the entire hour.

Yet at a time when civilization is accelerating toward disaster, climate silence continues to reign across the bulk of the US news media. Especially on television, where most Americans still get their news, the brutal demands of ratings and money work against adequate coverage of the biggest story of our time. Many newspapers, too, are failing the climate test. Last October, the scientists of the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released a landmark report, warning that humanity had a mere 12 years to radically slash greenhouse gas emissions or face a calamitous future in which hundreds of millions of people worldwide would go hungry or homeless or worse. Only 22 of the 50 biggest newspapers in the United States covered that report.

Instead of sleepwalking us toward disaster, the US news media need to remember their Paul Revere responsibilities – to awaken, inform and rouse the people to action. To that end, the Nation and CJR are launching Covering Climate Change: A New Playbook for a 1.5-Degree World, a project aimed at dramatically improving US media coverage of the climate crisis. When the IPCC scientists issued their 12-year warning, they said that limiting temperature rise to 1.5C would require radically transforming energy, agriculture, transportation, construction and other core sectors of the global economy. Our project is grounded in the conviction that the news sector must be transformed just as radically.

The project will launch on 30 April with a conference at the Columbia Journalism School – a working forum where journalists will gather to start charting a new course. We envision this event as the beginning of a conversation that America’s journalists and news organizations must have with one another, as well as with the public we are supposed to be serving, about how to cover this rapidly uncoiling emergency. Judging by the climate coverage to date, most of the US news media still don’t grasp the seriousness of this issue. There is a runaway train racing toward us, and its name is climate change. That is not alarmism; it is scientific fact. We as a civilization urgently need to slow that train down and help as many people off the tracks as possible. It’s an enormous challenge, and if we don’t get it right, nothing else will matter. The US mainstream news media, unlike major news outlets in Europe and independent media in the US, have played a big part in getting it wrong for many years. It’s past time to make amends.

If 1.5C is the new limit for a habitable planet, how can newsrooms tell that story in ways that will finally resonate with their audiences? And given journalism’s deeply troubled business model, how can such coverage be paid for? Some preliminary suggestions. (You can read this story in its entirety at Columbia Journalism Review or The Nation.)

Don’t blame the audience, and listen to the kids. The onus is on news organizations to craft the story in ways that will demand the attention of readers and viewers. The specifics of how to do this will vary depending on whether a given outlet works in text, radio, TV or some other medium and whether it is commercially or publicly funded, but the core challenge is the same. A majority of Americans are interested in climate change and want to hear what can be done about it. This is especially true of the younger people that news organizations covet as an audience. Even most young Republicans want climate action. And no one is speaking with more clarity now than Greta Thunberg, Alexandria Villaseñor and the other teenagers who have rallied hundreds of thousands of people into the streets worldwide for the School Strike 4 Climate demonstrations.

Establish a diverse climate desk, but don’t silo climate coverage. The climate story is too important and multidimensional for a news outlet not to have a designated team covering it. That team must have members who reflect the economic, racial and gender diversity of America; if not, the coverage will miss crucial aspects of the story and fail to connect with important audiences. At the same time, climate change is so far-reaching that connections should be made when reporting on nearly every topic. For example, an economics reporter could partner with a climate reporter to cover the case for a just transition: the need to help workers and communities that have long relied on fossil fuel, such as the coal regions of Appalachia, transition to a clean-energy economy, as the Green New Deal envisions.

Learn the science. Many journalists have long had a bias toward the conceptual. But you can’t do justice to the climate crisis if you don’t understand the scientific facts, in particular how insanely late the hour is. At this point, anyone suggesting a leisurely approach to slashing emissions is not taking the science seriously. Make the time to get educated. Four recent books – McKibben’s Falter, Naomi Klein’s On Fire, David Wallace-Wells’s The Uninhabitable Earth, and Jeff Goodell’s The Water Will Come – are good places to start.

Don’t internalize the spin. Not only do most Americans care about climate change, but an overwhelming majority support a Green New Deal – 81% of registered voters said so as of last December, according to Yale climate pollsters. Trump and Fox don’t like the Green New Deal? Fine. But journalists should report that the rest of America does. Likewise, they should not buy the argument that supporting a Green New Deal is a terrible political risk that will play into the hands of Trump and the GOP; nor should the media give credence to wild assertions about what a Green New Deal would do or cost. The data simply does not support such accusations. But breaking free from this ideological trap requires another step.

Lose the Beltway mindset. It’s not just the Green New Deal that is popular with the broader public. Many of the subsidiary policies – such as Medicare for All and free daycare – are now supported by upwards of 70% of the American public, according to Pew and Reuters polls. Inside the Beltway, this fact is unknown or discounted; the assumption by journalists and the politicians they cover is that such policies are ultra-leftist political suicide. They think this because the Beltway worldview prioritizes transactional politics: what will Congress pass and the president sign into law? But what Congress and the White House do is often very different from what the American people favor, and the press should not confuse the two.

Help the heartland. Some of the places being hit hardest by climate change, such as the midwestern states flooded this spring, have little access to real climate news; instead, the denial peddled by Fox News and Rush Limbaugh dominates. Iconic TV newsman Bill Moyers has an antidote: “Suppose you formed a consortium of media that could quickly act as a strike force to show how a disaster like this is related to climate change – not just for the general media, but for agricultural media, heartland radio stations, local television outlets. A huge teachable moment could be at hand if there were a small coordinating nerve center of journalists who could energize reporting, op-eds, interviews, and so on that connect the public to the causes and not just the consequences of events like this.” Moyers added that such a team should “always have on standby a pool of the most reputable scientists who, on camera and otherwise, can connect natural disasters to the latest and most credible scientific research”.

Cover the solutions. There isn’t a more exciting time to be on the climate beat. That may sound strange, considering how much suffering lies in store from the impacts that are already locked in. But with the Green New Deal, the US government is now, for the first time, at least talking about a response that is commensurate with the scale and urgency of the problem. Reporters have a tendency to gravitate to the crime scene, to the tragedy. They have a harder time with the solutions to a problem; some even mistake it as fluff. Now, with climate change, the solution is a critical part of the story.

Don’t be afraid to point fingers. As always, journalists should shun cheerleading, but neither should we be neutral. Defusing the climate crisis is in everyone’s interest, but some entities are resolutely opposed to doing what the science says is needed, starting with the president of the United States. The press has called out Trump on many fronts – for his lying, corruption and racism – but his deliberate worsening of the climate crisis has been little mentioned, though it is arguably the most consequential of his presidential actions. Meanwhile, ExxonMobil has announced plans to keep producing large amounts of oil and gas through at least 2040; other companies have made similar declarations. If enacted, those plans guarantee catastrophe. Journalism has a responsibility to make that consequence clear to the public and to cover the companies, executives, and investors behind those plans accordingly.

Advertisement

If American journalism doesn’t get the climate story right – and soon – no other story will matter. The news media’s past climate failures can be redeemed only by an immediate shift to more high-profile, inclusive and fearless coverage. Our #CoveringClimateNow project calls on all journalists and news outlets to join the conversation about how to make that happen. As the nation’s founders envisioned long ago, the role of a free press is to inform the people and hold the powerful accountable. These days, our collective survival demands nothing less.

(Source: The Guardian)

Last summer, during the deadliest wildfire season in California’s history, MSNBC’s Chris Hayes got into a revealing Twitter discussion about why US television doesn’t much cover climate change. Elon Green, an editor at Longform, had tweeted, “Sure would be nice if our news networks – the only outlets that can force change in this country – would cover it with commensurate urgency.” Hayes (who is an editor at large for the Nation) replied that his program had tried. Which was true: in 2016, All In With Chris Hayes spent an entire week highlighting the impact of climate change in the US as part of a look at the issues that Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump were ignoring. The problem, Hayes tweeted, was that “every single time we’ve covered [climate change] it’s been a palpable ratings killer. So the incentives are not great.”

The Twittersphere pounced. “TV used to be obligated to put on programming for the public good even if it didn’t get good ratings. What happened to that?” asked @JThomasAlbert. @GalJaya said, “Your ‘ratings killer’ argument against covering #climatechange is the reverse of that used during the 2016 primary when corporate media justified gifting Trump $5 billion in free air time because ‘it was good for ratings,’ with disastrous results for the nation.”

When @mikebaird17 urged Hayes to invite Katharine Hayhoe of Texas Tech University, one of the best climate science communicators around, on to his show, she tweeted that All In had canceled on her twice – once when “I was literally in the studio w[ith] the earpiece in my ear” – and so she wouldn’t waste any more time on it.

“Wait, we did that?” Hayes tweeted back. “I’m very very sorry that happened.”

This spring Hayes redeemed himself, airing perhaps the best coverage on American television yet of the Green New Deal. All In devoted its entire 29 March broadcast to analyzing the congressional resolution, co-sponsored by Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Senator Ed Markey, which outlines a plan to mobilize the United States to stave off climate disaster and, in the process, create millions of green jobs. In a shrewd answer to the ratings challenge, Hayes booked Ocasio-Cortez, the most charismatic US politician of the moment, for the entire hour.

Yet at a time when civilization is accelerating toward disaster, climate silence continues to reign across the bulk of the US news media. Especially on television, where most Americans still get their news, the brutal demands of ratings and money work against adequate coverage of the biggest story of our time. Many newspapers, too, are failing the climate test. Last October, the scientists of the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released a landmark report, warning that humanity had a mere 12 years to radically slash greenhouse gas emissions or face a calamitous future in which hundreds of millions of people worldwide would go hungry or homeless or worse. Only 22 of the 50 biggest newspapers in the United States covered that report.

Instead of sleepwalking us toward disaster, the US news media need to remember their Paul Revere responsibilities – to awaken, inform and rouse the people to action. To that end, the Nation and CJR are launching Covering Climate Change: A New Playbook for a 1.5-Degree World, a project aimed at dramatically improving US media coverage of the climate crisis. When the IPCC scientists issued their 12-year warning, they said that limiting temperature rise to 1.5C would require radically transforming energy, agriculture, transportation, construction and other core sectors of the global economy. Our project is grounded in the conviction that the news sector must be transformed just as radically.

The project will launch on 30 April with a conference at the Columbia Journalism School – a working forum where journalists will gather to start charting a new course. We envision this event as the beginning of a conversation that America’s journalists and news organizations must have with one another, as well as with the public we are supposed to be serving, about how to cover this rapidly uncoiling emergency. Judging by the climate coverage to date, most of the US news media still don’t grasp the seriousness of this issue. There is a runaway train racing toward us, and its name is climate change. That is not alarmism; it is scientific fact. We as a civilization urgently need to slow that train down and help as many people off the tracks as possible. It’s an enormous challenge, and if we don’t get it right, nothing else will matter. The US mainstream news media, unlike major news outlets in Europe and independent media in the US, have played a big part in getting it wrong for many years. It’s past time to make amends.

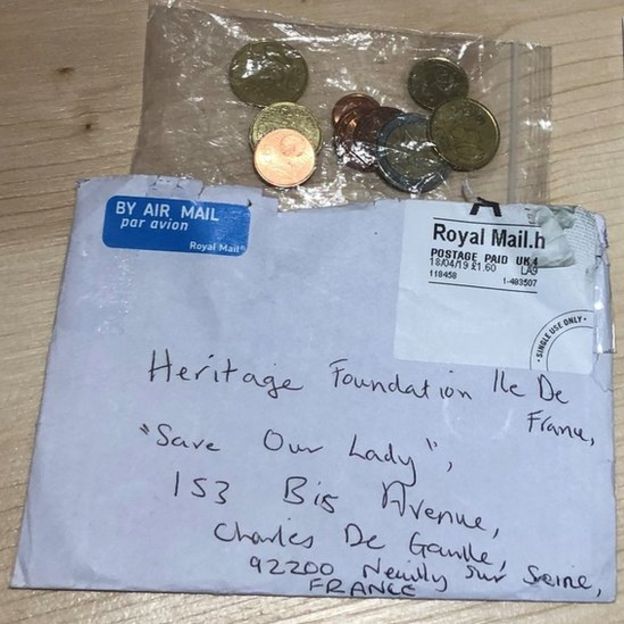

|

| A firefighter sprays water as flames from the Camp Fire consume a home in Magalia, California, in 2018 Photograph: Noah Berger/AP |

If 1.5C is the new limit for a habitable planet, how can newsrooms tell that story in ways that will finally resonate with their audiences? And given journalism’s deeply troubled business model, how can such coverage be paid for? Some preliminary suggestions. (You can read this story in its entirety at Columbia Journalism Review or The Nation.)

Don’t blame the audience, and listen to the kids. The onus is on news organizations to craft the story in ways that will demand the attention of readers and viewers. The specifics of how to do this will vary depending on whether a given outlet works in text, radio, TV or some other medium and whether it is commercially or publicly funded, but the core challenge is the same. A majority of Americans are interested in climate change and want to hear what can be done about it. This is especially true of the younger people that news organizations covet as an audience. Even most young Republicans want climate action. And no one is speaking with more clarity now than Greta Thunberg, Alexandria Villaseñor and the other teenagers who have rallied hundreds of thousands of people into the streets worldwide for the School Strike 4 Climate demonstrations.

Establish a diverse climate desk, but don’t silo climate coverage. The climate story is too important and multidimensional for a news outlet not to have a designated team covering it. That team must have members who reflect the economic, racial and gender diversity of America; if not, the coverage will miss crucial aspects of the story and fail to connect with important audiences. At the same time, climate change is so far-reaching that connections should be made when reporting on nearly every topic. For example, an economics reporter could partner with a climate reporter to cover the case for a just transition: the need to help workers and communities that have long relied on fossil fuel, such as the coal regions of Appalachia, transition to a clean-energy economy, as the Green New Deal envisions.

Learn the science. Many journalists have long had a bias toward the conceptual. But you can’t do justice to the climate crisis if you don’t understand the scientific facts, in particular how insanely late the hour is. At this point, anyone suggesting a leisurely approach to slashing emissions is not taking the science seriously. Make the time to get educated. Four recent books – McKibben’s Falter, Naomi Klein’s On Fire, David Wallace-Wells’s The Uninhabitable Earth, and Jeff Goodell’s The Water Will Come – are good places to start.

Don’t internalize the spin. Not only do most Americans care about climate change, but an overwhelming majority support a Green New Deal – 81% of registered voters said so as of last December, according to Yale climate pollsters. Trump and Fox don’t like the Green New Deal? Fine. But journalists should report that the rest of America does. Likewise, they should not buy the argument that supporting a Green New Deal is a terrible political risk that will play into the hands of Trump and the GOP; nor should the media give credence to wild assertions about what a Green New Deal would do or cost. The data simply does not support such accusations. But breaking free from this ideological trap requires another step.

Lose the Beltway mindset. It’s not just the Green New Deal that is popular with the broader public. Many of the subsidiary policies – such as Medicare for All and free daycare – are now supported by upwards of 70% of the American public, according to Pew and Reuters polls. Inside the Beltway, this fact is unknown or discounted; the assumption by journalists and the politicians they cover is that such policies are ultra-leftist political suicide. They think this because the Beltway worldview prioritizes transactional politics: what will Congress pass and the president sign into law? But what Congress and the White House do is often very different from what the American people favor, and the press should not confuse the two.

Help the heartland. Some of the places being hit hardest by climate change, such as the midwestern states flooded this spring, have little access to real climate news; instead, the denial peddled by Fox News and Rush Limbaugh dominates. Iconic TV newsman Bill Moyers has an antidote: “Suppose you formed a consortium of media that could quickly act as a strike force to show how a disaster like this is related to climate change – not just for the general media, but for agricultural media, heartland radio stations, local television outlets. A huge teachable moment could be at hand if there were a small coordinating nerve center of journalists who could energize reporting, op-eds, interviews, and so on that connect the public to the causes and not just the consequences of events like this.” Moyers added that such a team should “always have on standby a pool of the most reputable scientists who, on camera and otherwise, can connect natural disasters to the latest and most credible scientific research”.

Cover the solutions. There isn’t a more exciting time to be on the climate beat. That may sound strange, considering how much suffering lies in store from the impacts that are already locked in. But with the Green New Deal, the US government is now, for the first time, at least talking about a response that is commensurate with the scale and urgency of the problem. Reporters have a tendency to gravitate to the crime scene, to the tragedy. They have a harder time with the solutions to a problem; some even mistake it as fluff. Now, with climate change, the solution is a critical part of the story.

Don’t be afraid to point fingers. As always, journalists should shun cheerleading, but neither should we be neutral. Defusing the climate crisis is in everyone’s interest, but some entities are resolutely opposed to doing what the science says is needed, starting with the president of the United States. The press has called out Trump on many fronts – for his lying, corruption and racism – but his deliberate worsening of the climate crisis has been little mentioned, though it is arguably the most consequential of his presidential actions. Meanwhile, ExxonMobil has announced plans to keep producing large amounts of oil and gas through at least 2040; other companies have made similar declarations. If enacted, those plans guarantee catastrophe. Journalism has a responsibility to make that consequence clear to the public and to cover the companies, executives, and investors behind those plans accordingly.

Advertisement

If American journalism doesn’t get the climate story right – and soon – no other story will matter. The news media’s past climate failures can be redeemed only by an immediate shift to more high-profile, inclusive and fearless coverage. Our #CoveringClimateNow project calls on all journalists and news outlets to join the conversation about how to make that happen. As the nation’s founders envisioned long ago, the role of a free press is to inform the people and hold the powerful accountable. These days, our collective survival demands nothing less.

(Source: The Guardian)