The author longs to meet Shabari , not just the self-effacing old woman but also her free-spirited younger self, who displayed immense grace under pressure

I was rather young when I first heard of Shabari. My grandparents presented us with variations from Valmiki’s 2,000-year-old narration (Sarga 69 of the Aranyakanda) and from the 800-year-old Kamban Ramayana written in Tamil. Their Shabari was an elderly woman, a disciple of Rishi Matanga. When informed by Matanga that it was time for him to leave behind his mortal frame, Shabari had wanted to follow suit. Dissuading her, he instructed her to await Vishnu’s visit in human form and extend hospitality to Rama before embarking on her journey. Shabari was a kind-hearted and affectionate host who fed Rama and Lakshmana and then voluntarily relinquished her life.

Shabari’s life in the idyllic landscape of Lake Pampa, beside the Rishyamukha Mountain, was fascinating. The sand around the lake was soft and easy to walk upon. Abundant fruit and fish and boar provided for varied appetites to feed upon. Lotuses bloomed in profusion and birds nestled on trees. Possibly this was somewhere near modern-day Hampi, which still remains scenic and salubrious, despite continued human depredations.

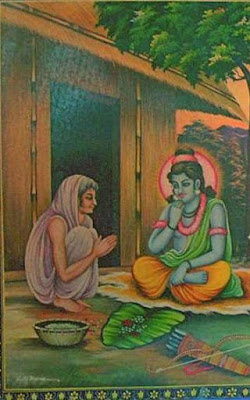

|

A prayer: Rama’s acceptance of the jujube fruits oered by Shabari repudiated caste hierarchies - WIKIMEDIA COMMONS |

The weather was delightful all year round, and Shabari recalled for me the grandmothers we stayed with in Chennai and Chidambaram in the long summer vacations when we escaped from the brutal Delhi heat and the monotonous everyday schedules of school. My grandmothers were steeped in the Bhakti tradition, which translated into the devoted attention they extended in everyday life to all their near and dear ones.

I am sure that for them, in the mellow autumn of their lives, Shabari was a significant point of reference: She had made the ashram a welcoming place and the warmth and generosity extended to her visitors knew no bounds. Modelling themselves on Shabari, my grandmothers were extraordinary reservoirs of nurture and warmth, as they bustled around visiting families, making them feel welcome and presenting them with the delicious fruits growing in and around their homes.

I was a little older when I learnt that Sabara was a noun that described a socially disadvantaged community to which Shabari belonged, quite unlike the rishis and kshatriya princes she served with selfless devotion. If I ever meet Shabari, perhaps I’d ask her what she felt about another woman of a disadvantaged caste — brutalised and killed in Uttar Pradesh last month.

Some 500 years ago, in the Adhyatma Ramayana, Shabari speaks of her spiritual unworthiness due to her low status, and awaits Rama’s reassurance of its irrelevance before immolating herself to attain liberation. The Adhyatma Ramayana records the increasing rigidity of caste hierarchies while confirming the lowly status of women in the patriarchal society. By this time, the considerate and compassionate Shabari became for me the lode-stone of integral human values such as selfless nurture and unconditional love, which were increasingly being jettisoned.

My mother explained how the ecchal ber (jujube fruits touched by human saliva) that Rama accepted and consumed not only repudiated caste hierarchies but also how Shabari’s gesture broke with antediluvian practices. It was Balram Das’s 15th-century Dandi Ramayana (in Odiya) that first mentioned the jhoota (saliva-touched) fruit as mangoes.

Arguably, this version of the saliva-flecked ber exists as oral narrative all over the Indian subcontinent, to provide direction. I’d like to discuss with Shabari the ‘touch-ability’ and ‘taste-ability’ she invokes through her biting into each individual fruit. It is, after all, an extraordinary metaphor reminding us of the urgent human imperative to transform and transcend hateful structures of class, caste, gender and race to a more egalitarian space.

An undocumented tale mentions the wealthy tribe Shabari had fled from in the days prior to her marriage, aghast at the wasteful culling of animals for the wedding feast, to seek refuge at Matanga’s ashram. It would be fascinating to discuss this with the younger Shabari, who rejected conjugality as defining or completing female identity. Shabari followed her heart’s desire and is a significant female role model, whose intellectual and spiritual prowess outranked or was on par with patriarchal men. Contributing to sustainable living and careful about what she consumed; she remained courteous and hospitable, while standing her ground in the face of great odds. Was she not victimised in those beautiful ancient environs for her free thinking, for her youth, for her lower social status, for being a woman, for wanting to be different? Shabari must have been made to suffer.

Although posterity has chosen to enshrine only the self-effacing aged woman, I have longed to meet the free-spirited young woman who valued goodwill and nurture as an intrinsic and extended largesse to all sentient beings, while displaying extraordinary qualities of grace and dignity under pressure. It is the countless articulate Shabaris around us — old, middle-aged, and young — that I continue to seek. May their tribe increase.

(Source: Business Line)

No comments:

Post a Comment