Art, it appeared, had imitated life. His 18-year-old daughter said he had been raping her for years, writes Laura Smith in Timeline. Read on:

It seemed that there was nothing that could shock Hustler readers anymore. Larry Flynt, the magazine’s publisher, was the “the sultan of smut” who rejoiced in pushing every Puritanical button this country had. One cover once infamously depicted a woman being run through a meat grinder alongside the words “We will no longer hang women up like pieces of meat.”

Hustler once dubbed feminist Andrea Dworkin a “shit-squeezing sphincter.” Nothing was out of bounds: shit, farts, assholes, you name it. As Laura Kipnis explained in her book on pornography, Bound and Gagged, “From its inception, Hustler made it its mission to disturb and unsettle its readers.” But one column provoked in a way that Flynt hadn’t intended.

The “Chester the Molester” cartoon first appeared in Hustler’s pages in 1976. The origin of the term many of us grew up using jokingly, the strip starred Chester, a beefy middle-aged man shown in various pedophilic acts — concealing his genitals in a hot dog bun while offering it to a child or, in a twist on the famous Coppertone sunscreen logo, Chester tugged at a little girl’s bathing suit with his teeth.

Then in 1989, the cartoon’s creator, Dwaine B. Tinsley, was arrested. Art, it appeared, had imitated life. His 18-year-old daughter said he had been raping her for years. Like the purloined letter, it seemed that Tinsley was hiding in plain sight.

Tinsley’s case had many wondering about the culture of a place that had promoted this man. Upon hearing the news, one of her father’s colleagues remarked, “I’d do her,” then added, “Not if I was her dad.”

The daughter reported that many of the scenes depicted in Tinsley’s stip were directly drawn from things he had done to her. Tinsley could legally draw whatever he wanted for sure, but what if these drawings had been used as a means of psychological damage on his victim? This was more than a free speech case — if true, Tinsley had committed a crime — but the cartoons were inextricably bound up in the crime.

The only lengthy treatment of the case is the book, Most Outrageous, by Bob Levin. As Levin explains, “Veronica’s” story went like this: Tinsley’s sexual abuse began at a hotel when she was 11. Then, when she was 13, she moved in with her father to escape her abusive mother and that was when Tinsley began having sex with her two to five times a week for five years. In May of 1989, at the urging of a boyfriend when she was 18, she reported the abuse.

The detectives told her to call her father and try to get him to admit to it, while they secretly recorded the conversation in what is known as a “cool call.” At first, Tinsley played dumb. But when she said, “I’m talking about the sex,” he replied, “Veronica, I don’t want to talk about that. I don’t want to talk about that at all.”

When she pressed him further he said, “Veronica, listen. I am not going to talk to you about this over the phone.” He then proceeded to tell her to stop thinking about it because he didn’t think about it, and said she was hurting him. The detectives were satisfied. He hadn’t outright admitted it, but not denying it looked pretty damning.

The next day, police pulled him over in his Mustang in Simi Valley, California. Tinsley said he had caught her using coke and she was retaliating. She was trying to extort him for an old Isuzu.

The trial began in December of 1989. Veronica told the jury that she had submitted to the sexual encounters because “I felt like this is what I had to do in order for my father to show me love and attention.”

Tinsley explained that he hadn’t contradicted his daughter on the “cool call” because he was concerned about her drug use and that she had previously threatened to find ways to hurt him. Even if these things were true, it’s hard to imagine how anyone would allow such an inflammatory claim — incest — to be met with anything other than full-throated denial. Levin, however, seemed to buy Tinsley’s explanation, writing, “the conversation assumes a less definitive cast.”

Though Tinsley wouldn’t admit this at the trial, one of the notes kept by his wife partially corroborated the first incident. It occurred in a Los Angeles hotel room, but in his version the 11 year-old had initiated the sexual contact. He said he had been sleeping and in a semi-awake state he had felt “a warm soft feminine body pushed against me. I cuddled and stroked the legs and hips. Suddenly I sprang awake and jumped. I realized it was Veronica — my daughter! I was mortified … The whole episode bugged me for many years. I finally came to grips with the fact that I had done nothing wrong.”

He would later admit to other incidents that at best seemed extreme lapses in judgement, at worst telltale signs of sexual abuse: drunkenly falling asleep in her bed, entering her room while she was sleeping in the nude.

It was Veronica’s word against Tinsley and neither looked very good. Tinsley drew lewd pictures of men abusing little girls. Veronica had behavioral problems in school and a cocaine habit. There were inconsistencies in her story about the timeline of events. To some, these inconsistencies and “character” issues were the obvious scars of an entire adolescence riddled with sexual trauma. To others, it was the proof of an instability that had manufactured a claim at an easy target — someone whose association with pedophilia found its way into millions of mailboxes all over the country every month.

The accusations against Tinsley came at a time of hypervigilance about child sexual abuse. The McMartin Preschool trials — where Los Angeles nursery school teachers were accused (wrongly, it turned out) of sexually abusing children in satanic rituals — were going on simultaneous to Tinsley’s trial.

Stories about both trials often ran on the same page in newspapers. A few years earlier, the Catholic church had entered the national spotlight when a priest admitted to molesting 37 boys, and soon other similar claims followed. The same year of Tinsley’s trial, an article ran in the Toronto Star proclaiming “Sex with children is the crime of the moment.”

In many places in his book, Levin argued that it was Tinsley’s ideas that were on trial. “What about the ways of life of authors who traffic in homicide and mayhem and other socially disapproved sexual actions?” Levin wrote. “What actions may have been incubating in the homes of Norman Mailer and Cormac McCarthy and Joyce Carol Oates…?” The response to this is obvious: it doesn’t matter because no one had accused McCarthy or Oates of murder.

Levin argued there was reason to doubt Veronica’s story because a search warrant turned up none of the keepsakes or relics that pedophiles typically keep — a fact that seems hardly exculpating. When Veronica was examined for forced sexual abuse, Levin merely concluded in passing, “(there was none),” nevermind that their last sex act was six months prior, and that Veronica reported submitting to the acts, so signs of forced abuse were unlikely to be found.

As for the fact that Tinsley took his daughter to a psychotherapist at one point, Levin writes, “that alone seemed to me to acquit him.”

The jury did not agree. On January 5th, 1990 the jury convicted him on five counts, acquitted him of six, and deadlocked on the remaining five. The judge declined to impose the maximum 12-year sentence “out of consideration for the defendant’s wife and two daughters,” a strange line of reasoning considering that he had been convicted of molesting his other daughter.

The judge didn’t see Tinsley as a threat to other children, though how he could be confident of this, is hard to say.

Levin was right about one thing: cartoons didn’t mean he was a pedophile, but they didn’t make him look good. The judge had permitted them to be presented in court on the grounds that Veronica claimed she was forced to be surrounded by them. But, it’s reasonable see that as a tactic by the prosecution to bias the jury against Tinsley. The cartoons were intended to make people squirm. But were they relevant to the alleged crime?

Two years later, another judged reversed the conviction on appeal. Showing the cartoons in the courtroom had been gratuitous and unfairly biased the jurors, the judge said. In a strange reversal, the very drawings that appeared to originally incriminate him now exonerated him. By February of 1992, he was walking free.

Tinsley could have been retried, but the judge dropped the charges at the request of the prosecutor. The prosecutor said of Veronica, “She has struggled over the years to overcome the personal problems that resulted from her abuse and does not want to have them brought up again.” It was an unsatisfying ending any way you looked at it.

If Tinsley was telling the truth, he never really got to be exonerated in court. If Veronica was, her abuser walked free. Tinsley died in 2000. Perhaps the only victory was for the First Amendment, which affirmed the message that the porn industry had been sending the world for decades: don’t mess with smut in court.

It seemed that there was nothing that could shock Hustler readers anymore. Larry Flynt, the magazine’s publisher, was the “the sultan of smut” who rejoiced in pushing every Puritanical button this country had. One cover once infamously depicted a woman being run through a meat grinder alongside the words “We will no longer hang women up like pieces of meat.”

Hustler once dubbed feminist Andrea Dworkin a “shit-squeezing sphincter.” Nothing was out of bounds: shit, farts, assholes, you name it. As Laura Kipnis explained in her book on pornography, Bound and Gagged, “From its inception, Hustler made it its mission to disturb and unsettle its readers.” But one column provoked in a way that Flynt hadn’t intended.

The “Chester the Molester” cartoon first appeared in Hustler’s pages in 1976. The origin of the term many of us grew up using jokingly, the strip starred Chester, a beefy middle-aged man shown in various pedophilic acts — concealing his genitals in a hot dog bun while offering it to a child or, in a twist on the famous Coppertone sunscreen logo, Chester tugged at a little girl’s bathing suit with his teeth.

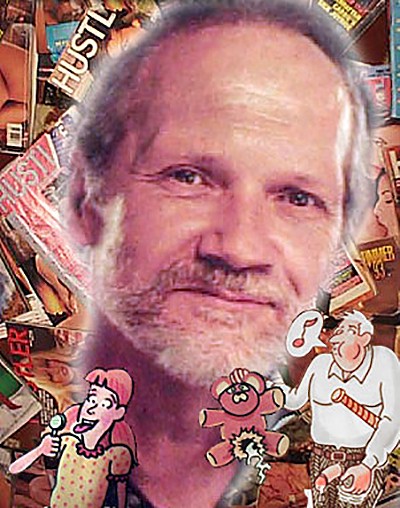

|

| A 1983 comic for Hustler Humor by Dwaine Tinsley. |

Tinsley’s case had many wondering about the culture of a place that had promoted this man. Upon hearing the news, one of her father’s colleagues remarked, “I’d do her,” then added, “Not if I was her dad.”

The daughter reported that many of the scenes depicted in Tinsley’s stip were directly drawn from things he had done to her. Tinsley could legally draw whatever he wanted for sure, but what if these drawings had been used as a means of psychological damage on his victim? This was more than a free speech case — if true, Tinsley had committed a crime — but the cartoons were inextricably bound up in the crime.

The only lengthy treatment of the case is the book, Most Outrageous, by Bob Levin. As Levin explains, “Veronica’s” story went like this: Tinsley’s sexual abuse began at a hotel when she was 11. Then, when she was 13, she moved in with her father to escape her abusive mother and that was when Tinsley began having sex with her two to five times a week for five years. In May of 1989, at the urging of a boyfriend when she was 18, she reported the abuse.

The detectives told her to call her father and try to get him to admit to it, while they secretly recorded the conversation in what is known as a “cool call.” At first, Tinsley played dumb. But when she said, “I’m talking about the sex,” he replied, “Veronica, I don’t want to talk about that. I don’t want to talk about that at all.”

When she pressed him further he said, “Veronica, listen. I am not going to talk to you about this over the phone.” He then proceeded to tell her to stop thinking about it because he didn’t think about it, and said she was hurting him. The detectives were satisfied. He hadn’t outright admitted it, but not denying it looked pretty damning.

The next day, police pulled him over in his Mustang in Simi Valley, California. Tinsley said he had caught her using coke and she was retaliating. She was trying to extort him for an old Isuzu.

The trial began in December of 1989. Veronica told the jury that she had submitted to the sexual encounters because “I felt like this is what I had to do in order for my father to show me love and attention.”

Tinsley explained that he hadn’t contradicted his daughter on the “cool call” because he was concerned about her drug use and that she had previously threatened to find ways to hurt him. Even if these things were true, it’s hard to imagine how anyone would allow such an inflammatory claim — incest — to be met with anything other than full-throated denial. Levin, however, seemed to buy Tinsley’s explanation, writing, “the conversation assumes a less definitive cast.”

Though Tinsley wouldn’t admit this at the trial, one of the notes kept by his wife partially corroborated the first incident. It occurred in a Los Angeles hotel room, but in his version the 11 year-old had initiated the sexual contact. He said he had been sleeping and in a semi-awake state he had felt “a warm soft feminine body pushed against me. I cuddled and stroked the legs and hips. Suddenly I sprang awake and jumped. I realized it was Veronica — my daughter! I was mortified … The whole episode bugged me for many years. I finally came to grips with the fact that I had done nothing wrong.”

He would later admit to other incidents that at best seemed extreme lapses in judgement, at worst telltale signs of sexual abuse: drunkenly falling asleep in her bed, entering her room while she was sleeping in the nude.

It was Veronica’s word against Tinsley and neither looked very good. Tinsley drew lewd pictures of men abusing little girls. Veronica had behavioral problems in school and a cocaine habit. There were inconsistencies in her story about the timeline of events. To some, these inconsistencies and “character” issues were the obvious scars of an entire adolescence riddled with sexual trauma. To others, it was the proof of an instability that had manufactured a claim at an easy target — someone whose association with pedophilia found its way into millions of mailboxes all over the country every month.

|

| Dwaine Tinsley was a comic artist who’s work may have eluded to troubling real life events. |

Stories about both trials often ran on the same page in newspapers. A few years earlier, the Catholic church had entered the national spotlight when a priest admitted to molesting 37 boys, and soon other similar claims followed. The same year of Tinsley’s trial, an article ran in the Toronto Star proclaiming “Sex with children is the crime of the moment.”

In many places in his book, Levin argued that it was Tinsley’s ideas that were on trial. “What about the ways of life of authors who traffic in homicide and mayhem and other socially disapproved sexual actions?” Levin wrote. “What actions may have been incubating in the homes of Norman Mailer and Cormac McCarthy and Joyce Carol Oates…?” The response to this is obvious: it doesn’t matter because no one had accused McCarthy or Oates of murder.

Levin argued there was reason to doubt Veronica’s story because a search warrant turned up none of the keepsakes or relics that pedophiles typically keep — a fact that seems hardly exculpating. When Veronica was examined for forced sexual abuse, Levin merely concluded in passing, “(there was none),” nevermind that their last sex act was six months prior, and that Veronica reported submitting to the acts, so signs of forced abuse were unlikely to be found.

As for the fact that Tinsley took his daughter to a psychotherapist at one point, Levin writes, “that alone seemed to me to acquit him.”

The jury did not agree. On January 5th, 1990 the jury convicted him on five counts, acquitted him of six, and deadlocked on the remaining five. The judge declined to impose the maximum 12-year sentence “out of consideration for the defendant’s wife and two daughters,” a strange line of reasoning considering that he had been convicted of molesting his other daughter.

The judge didn’t see Tinsley as a threat to other children, though how he could be confident of this, is hard to say.

Levin was right about one thing: cartoons didn’t mean he was a pedophile, but they didn’t make him look good. The judge had permitted them to be presented in court on the grounds that Veronica claimed she was forced to be surrounded by them. But, it’s reasonable see that as a tactic by the prosecution to bias the jury against Tinsley. The cartoons were intended to make people squirm. But were they relevant to the alleged crime?

Two years later, another judged reversed the conviction on appeal. Showing the cartoons in the courtroom had been gratuitous and unfairly biased the jurors, the judge said. In a strange reversal, the very drawings that appeared to originally incriminate him now exonerated him. By February of 1992, he was walking free.

Tinsley could have been retried, but the judge dropped the charges at the request of the prosecutor. The prosecutor said of Veronica, “She has struggled over the years to overcome the personal problems that resulted from her abuse and does not want to have them brought up again.” It was an unsatisfying ending any way you looked at it.

If Tinsley was telling the truth, he never really got to be exonerated in court. If Veronica was, her abuser walked free. Tinsley died in 2000. Perhaps the only victory was for the First Amendment, which affirmed the message that the porn industry had been sending the world for decades: don’t mess with smut in court.

No comments:

Post a Comment