As the courts decide whether Indians have a "right to privacy," the real battle rages on in living rooms and principal's offices.

The plain truth is this: Indians do not care about privacy. This isn’t an accusation, it's a fact.

As a lawyer representing the Indian government in a privacy case recently said, Indians cannot “import conceptions of privacy” because “on a train in this country, people will tell you their life stories within five minutes”.

When I was in the 11th grade, I was called in to the principal's office after class one day. One of my classmates was waiting outside, grinning widely. He was also sweating profusely and nervously rubbing his palms together. Something was off.

When I asked him what was going on, he said that they had taken his Facebook password from him and had gone through all his chats. I realised that he probably wasn’t smiling because he was happy. He was freaking out and the grin was an attempt to hold back tears.

I didn't believe him though. I thought he had voluntarily offered his password just to prove a point. Then, I was called in.

Indian society is based on communities, not individuals. In fact, there is no word for privacy in most Indian languages .

The principal and his daughter had just left, leaving the vice-principal to deal with me. "Aroon Deep, your Facebook password," she commanded in a deadpan voice, handing me a post-it note and a pen. Standing around me were three teachers and the school's IT guy.

I said no.

Taken aback, the vice-principal persisted, threatening to expel me from school if I didn’t comply. Eventually, she made me call my parents.

The principal’s daughter was rumoured to be seeing a senior, and this being a conservative South Indian school, an ‘investigation’ had been ordered. I barely knew the girl, but for reasons unknown to me to this day, my Facebook account had been identified as an important part of this investigation.

There is no word in most Indian languages for privacy. That isn’t surprising, considering that unlike many western countries, Indian society is based on communities, not individuals.

We are a country of joint families — where cousins live under the same roof and grow up as siblings and having a room to yourself is a rare privilege. Privacy has never been something Indians have enjoyed, so it is not as much of a priority as it is for, let’s say, Americans, who tend to live in nuclear families.

With my parents en route, I was made to wait outside the office. The vice-principal and her coterie took turns to come outside and play good-cop bad-cop in an attempt to get me to hand my password over. I didn’t relent.

When my parents finally arrived, they assured me that they would get me out of this. The vice-principal called them in to brief them with scary tales of a Brahmin girl's dignity being at risk.

I don’t know what transpired in that meeting, but by the end of it, my parents were convinced that protecting my privacy wasn’t as important as ending a possible fling that I had nothing to do with.

I had been waiting for hours and was fatigued. They began nagging me to hand my password over, because "what's the worst that could happen?"

I gave in.

The next day, I was expelled.

In a time when government websites leak the personal details of 135 million citizens with no consequences, when a database of 120 million mobile users can be leaked without so much as a peep on newspaper front pages, a strong privacy law is clearly a fundamental requirement.

Had such a law existed, this may have not happened. My school may have known better than to ask for students’ social media passwords, and I may have been in a better position to refuse to give it to them. The lack of legal protection aside, the weight of a culture that had no value for the concept of privacy meant that I was powerless to resist an invasion of my personal space.

Meanwhile, a fifteen-year-old on the other side of the planet was going through the same thing – she was forced to watch as school administrators logged into her Facebook account after forcing her password out of her. In her case, the largest civil liberties union in the US sued the school and the court ordered them to pay up $70,000 in damages.

I had no such luck.

The entire incident was deeply disturbing and has had a profound effect on how I behave online.

The night before my expulsion, the vice-principal and a team of teachers pored over my personal conversations. None of them had anything to do with the principal’s daughter. However, they did find messages where I had called the principal some less-than-pleasant names, and ‘conspired’ to send spam to his inbox from an anonymous email address. They forced their way into a teenager’s unfiltered private ramblings and put them on trial.

The entire incident was deeply disturbing and has had a profound effect on how I behave online. As a teenager who was very active on social media, my Facebook account was a huge part of who I was as a person. I had the key to my identity ripped away from me and used against me.

In the months that followed, my parents and I went through hell. Screenshots of my swear-ridden chats were circulated among the teachers and to my parents to justify my expulsion. They were obviously more upset about the things that I had said than what had happened to me (referring to the principal’s baldness with an expletive doesn't look too good, I'll admit).

It was unlikely that my expulsion was ever permanent — kicking out a 11th grader in a CBSE school is procedurally complicated and difficult to justify to higher-ups. However, the principal knew that I was completely at his mercy, and saw to it that I understood this very well.

Forget suing the school for expelling me without due process and violating my privacy, I was afraid to even open Facebook now. The school ‘banned’ me from social media as a condition for taking me back.

A few months before the incident, my principal had called me in after he found out that I had once brought my phone to class. “As an educator, I have every right to intrude upon students, I have a responsibility to,” he told me.

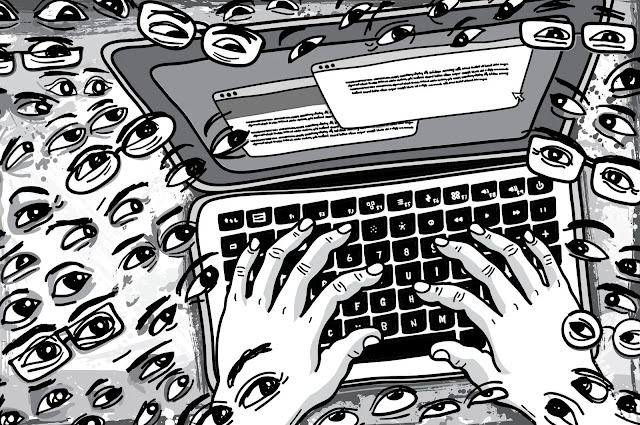

As I write this, a mammoth Supreme Court bench of nine judges is trying to decide whether privacy is a fundamental right under India’s constitution. I believe it is. The right to liberty is incomplete without our ability to be who we are away from the glare of those who wish to overpower us.

When the government doesn’t care about privacy while making its decisions, it risks the prospect of turning into a surveillance state. For the government to care about privacy, we need to care about privacy. Not just some journalists and policy wonks in high office, all of us.

Make no mistake – when the government asks for your Aadhaar for things like filing taxes, opening a bank account, and even graduating from college, they are not actively seeking to invade your privacy. They do these things as a lazy way out of having effective ways of dealing with fraudulent behaviour. Privacy is probably not even a consideration here.

The right to liberty is incomplete without our ability to be who we are away from the glare of those who wish to overpower us.

But those who don't know enough to care about the right to privacy risk being those who are hurt most by an India where it is not a consideration.

Young people using public WiFi authenticated with their phone number risk having everyone from Google to the Indian government maintaining a personaly identifiable log of what they do online. Underprivileged citizens whose Aadhaar numbers have leaked into the public domain risk having their data being used by scammers to siphon off government benefits that are rightfully theirs.

Companies are not required to be careful with data that they collect about their customers. The government isn’t required to exercise restraint in its data collection. Worst of all, nobody cares about what could happen to them with information they don’t even know is being collected about them.

We already live in an environment where catastrophic oversights like a tenth of all Indian citizens’ Aadhaar numbers being uploaded without protection on government websites are commonplace. And yet, we’re not debating how to make sure less data is available about us, or how to ensure that corporates and governments have a responsibility to keep information about us safe and use it as minimally as possible. Instead, the debate is about whether privacy is a fundamental right.

The Supreme Court’s decision on privacy will be a historic moment for India. But even if it turns out well, it will just be the beginning of a long and tiring battle. But as the fight rages on in the courtrooms and in parliament, the bigger battle will be fought in our homes and schools, as we attempt to convince parents and principals that a 15-year-old's right to a private life is important to the future of this country.

(Source: Buzzfeed)

The plain truth is this: Indians do not care about privacy. This isn’t an accusation, it's a fact.

As a lawyer representing the Indian government in a privacy case recently said, Indians cannot “import conceptions of privacy” because “on a train in this country, people will tell you their life stories within five minutes”.

When I was in the 11th grade, I was called in to the principal's office after class one day. One of my classmates was waiting outside, grinning widely. He was also sweating profusely and nervously rubbing his palms together. Something was off.

When I asked him what was going on, he said that they had taken his Facebook password from him and had gone through all his chats. I realised that he probably wasn’t smiling because he was happy. He was freaking out and the grin was an attempt to hold back tears.

I didn't believe him though. I thought he had voluntarily offered his password just to prove a point. Then, I was called in.

Indian society is based on communities, not individuals. In fact, there is no word for privacy in most Indian languages .

The principal and his daughter had just left, leaving the vice-principal to deal with me. "Aroon Deep, your Facebook password," she commanded in a deadpan voice, handing me a post-it note and a pen. Standing around me were three teachers and the school's IT guy.

I said no.

Taken aback, the vice-principal persisted, threatening to expel me from school if I didn’t comply. Eventually, she made me call my parents.

The principal’s daughter was rumoured to be seeing a senior, and this being a conservative South Indian school, an ‘investigation’ had been ordered. I barely knew the girl, but for reasons unknown to me to this day, my Facebook account had been identified as an important part of this investigation.

There is no word in most Indian languages for privacy. That isn’t surprising, considering that unlike many western countries, Indian society is based on communities, not individuals.

We are a country of joint families — where cousins live under the same roof and grow up as siblings and having a room to yourself is a rare privilege. Privacy has never been something Indians have enjoyed, so it is not as much of a priority as it is for, let’s say, Americans, who tend to live in nuclear families.

With my parents en route, I was made to wait outside the office. The vice-principal and her coterie took turns to come outside and play good-cop bad-cop in an attempt to get me to hand my password over. I didn’t relent.

When my parents finally arrived, they assured me that they would get me out of this. The vice-principal called them in to brief them with scary tales of a Brahmin girl's dignity being at risk.

I don’t know what transpired in that meeting, but by the end of it, my parents were convinced that protecting my privacy wasn’t as important as ending a possible fling that I had nothing to do with.

I had been waiting for hours and was fatigued. They began nagging me to hand my password over, because "what's the worst that could happen?"

I gave in.

The next day, I was expelled.

In a time when government websites leak the personal details of 135 million citizens with no consequences, when a database of 120 million mobile users can be leaked without so much as a peep on newspaper front pages, a strong privacy law is clearly a fundamental requirement.

Had such a law existed, this may have not happened. My school may have known better than to ask for students’ social media passwords, and I may have been in a better position to refuse to give it to them. The lack of legal protection aside, the weight of a culture that had no value for the concept of privacy meant that I was powerless to resist an invasion of my personal space.

Meanwhile, a fifteen-year-old on the other side of the planet was going through the same thing – she was forced to watch as school administrators logged into her Facebook account after forcing her password out of her. In her case, the largest civil liberties union in the US sued the school and the court ordered them to pay up $70,000 in damages.

I had no such luck.

The entire incident was deeply disturbing and has had a profound effect on how I behave online.

The night before my expulsion, the vice-principal and a team of teachers pored over my personal conversations. None of them had anything to do with the principal’s daughter. However, they did find messages where I had called the principal some less-than-pleasant names, and ‘conspired’ to send spam to his inbox from an anonymous email address. They forced their way into a teenager’s unfiltered private ramblings and put them on trial.

The entire incident was deeply disturbing and has had a profound effect on how I behave online. As a teenager who was very active on social media, my Facebook account was a huge part of who I was as a person. I had the key to my identity ripped away from me and used against me.

In the months that followed, my parents and I went through hell. Screenshots of my swear-ridden chats were circulated among the teachers and to my parents to justify my expulsion. They were obviously more upset about the things that I had said than what had happened to me (referring to the principal’s baldness with an expletive doesn't look too good, I'll admit).

It was unlikely that my expulsion was ever permanent — kicking out a 11th grader in a CBSE school is procedurally complicated and difficult to justify to higher-ups. However, the principal knew that I was completely at his mercy, and saw to it that I understood this very well.

Forget suing the school for expelling me without due process and violating my privacy, I was afraid to even open Facebook now. The school ‘banned’ me from social media as a condition for taking me back.

A few months before the incident, my principal had called me in after he found out that I had once brought my phone to class. “As an educator, I have every right to intrude upon students, I have a responsibility to,” he told me.

As I write this, a mammoth Supreme Court bench of nine judges is trying to decide whether privacy is a fundamental right under India’s constitution. I believe it is. The right to liberty is incomplete without our ability to be who we are away from the glare of those who wish to overpower us.

When the government doesn’t care about privacy while making its decisions, it risks the prospect of turning into a surveillance state. For the government to care about privacy, we need to care about privacy. Not just some journalists and policy wonks in high office, all of us.

Make no mistake – when the government asks for your Aadhaar for things like filing taxes, opening a bank account, and even graduating from college, they are not actively seeking to invade your privacy. They do these things as a lazy way out of having effective ways of dealing with fraudulent behaviour. Privacy is probably not even a consideration here.

The right to liberty is incomplete without our ability to be who we are away from the glare of those who wish to overpower us.

But those who don't know enough to care about the right to privacy risk being those who are hurt most by an India where it is not a consideration.

Young people using public WiFi authenticated with their phone number risk having everyone from Google to the Indian government maintaining a personaly identifiable log of what they do online. Underprivileged citizens whose Aadhaar numbers have leaked into the public domain risk having their data being used by scammers to siphon off government benefits that are rightfully theirs.

Companies are not required to be careful with data that they collect about their customers. The government isn’t required to exercise restraint in its data collection. Worst of all, nobody cares about what could happen to them with information they don’t even know is being collected about them.

We already live in an environment where catastrophic oversights like a tenth of all Indian citizens’ Aadhaar numbers being uploaded without protection on government websites are commonplace. And yet, we’re not debating how to make sure less data is available about us, or how to ensure that corporates and governments have a responsibility to keep information about us safe and use it as minimally as possible. Instead, the debate is about whether privacy is a fundamental right.

The Supreme Court’s decision on privacy will be a historic moment for India. But even if it turns out well, it will just be the beginning of a long and tiring battle. But as the fight rages on in the courtrooms and in parliament, the bigger battle will be fought in our homes and schools, as we attempt to convince parents and principals that a 15-year-old's right to a private life is important to the future of this country.

(Source: Buzzfeed)

No comments:

Post a Comment